The north-west of England in the 18th century was a hotbed of religious non-conformism. In particular, it was the birthplace of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, whose founder George Fox had a vision on Pendle Hill in Lancashire. The word “Quaker” was a pejorative nickname at first, an attempt to ridicule the piety of these strange non-conformists and the way they cowered before God, but it was eventually proudly worn by the Quakers themselves.

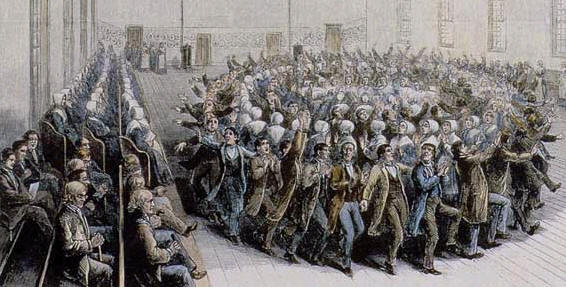

One sect that split from the Quakers in Lancashire were the Shakers, named in rhyming fashion for their continuation of an ecstatic style of worship at a time when mainstream Quakers were moving away from such charismatic practices.

Perhaps most notably, the Shakers believed in genuine equality between the sexes; their first real leader was Mother Ann Lee, who led the emigration of the Shakers to America in the 1770s and established a colony in New York.

The most enduring legacy of the Shakers isn’t their religious teaching, though, but rather their furniture. With a social code that emphasised hard work and craftsmanship, and an aesthetic belief that prioritised simple, elegant forms, Shaker furniture was prophetic in many ways of 20th-century modernist designs, and remains popular for that reason.

The Shakers’ commitment to gender equality and craftsmanship is perhaps best embodied by Tabitha Babbitt (1779–1853), a wonderfully named craftswoman who invented both the circular saw and a method for the mass manufacture of false teeth.